Dimensions of the Typology

In order to analyse and describe VET-systems, we need to consider the macro- , the meso- and the micro-level:

Macro-level

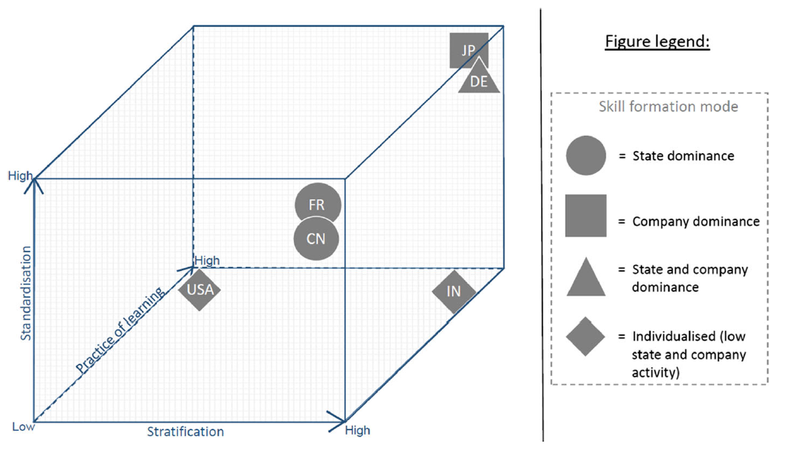

At the macro-level, the model differentiates between the skill formation approach and the stratification approach.

The skill formation approach focusses on the interaction between political and socio-economic institutions and other stakeholders in the VET context (Busemeyer & Trampusch 2012). In addition to the influence of stakeholders on VET policy, the issue of direct funding and financial involvement is also of crucial importance (Busemeyer & Trampusch 2012, p. 21). The skill formation model covers four characteristics of different constellations of stakeholders:

(1) the influence of the state on vocational education and training (“state-dominance”);

(2) the potential for activity by and influence from companies (“company-dominance”);

(3) Where both influences are limited, individual influence may be prioritised (“individualised”; for example, participation in individually funded training provision organised by the private sector);

(4) where state and companies have a high level of influence, this may be characterised as a mixed system (or “state and company dominance”).

These differing levels of activity produce different constellations of stakeholders that can then be illustrated in the form of a matrix.

In our approach, stratification forms part of the macro-level and relates to issues of “tracking” and of the marked differentiation of and separation between general training courses from vocational ones. The construct “stratification” (related to the education system) is adopted from the field of sociology where it is defined as “the extent and form of tracking that is pervasive in the educational system” (Shavit & Müller 2000, p. 443). The term “tracking” refers to pupils’ different trajectories through the school system, a view that takes in both the distinction between general and vocational education (and the different routes taken into them) and the differentiation of hierarchical levels by access, selection and transition mechanisms (Allmendinger 1989, p. 233).

Another relevant issue is “indirect stratification” (Pilz & Alexander 2011) resulting from the significance of rankings and league tables for education and training institutions. Stratification should also portray the status and image of vocational training courses within individual societies.

To simplify, “stratification” needs to be expressed in a duopolistic sense – as either “high” or “low”.

Meso-level

For the meso-level, we took up the concept of “standardisation” to describe how the structures and processes underpinning any vocational education and training system are standardised and made subject to binding regulation (Müller & Shavit 1998). Shavit and Müller (2000, p. 443) define standardisation as follows “(…) the degree to which the quality of education meets the same standards nationwide. Variables such as teacher training, school budgets, curricula, and the uniformity of school-leaving examinations are relevant in measuring standardisation.” Specifically, this element focuses not only on certification but also, and in particular, on curriculum, institutions and teaching staff. Standardisation is a duopolistic construct.

Micro-level

Thirdly, on the micro-level, the explicitly vocational-pedagogical perspective enters the equation. Here, the focus is specifically on the concrete relevance to vocational practice or to later roles within the employment system of the teaching and learning processes.

Learning processes

On the one hand, the learning content delivered may be analysed in relation to both its theoretical and its practical content. At operational level, this would, therefore, include aspects such as the skill acquisition expected as a result of a particular learning process or the selection and structuring of the topics covered and the balance between a technical skills orientation and a situational orientation. Of particular significance here is also the question of whether, as part of vocational learning processes, curricula produce a fragmentary and poorly integrated acquisition of skills or whether a system focuses instead on the acquisition of complete and complex performed actions in the context of situated learning (i.e. planning, implementation and review).

Teaching (practices)

The interaction and social relationships between teachers and learners (such as teacher-centred work versus group work or receptive learning versus discovery learning), the level of freedom learners have within the learning process (self-directed learning), and the individualisation of learning processes all play a part. Furthermore, the practical relevance of the media and methods used, including such teaching and learning arrangements as case studies, is also important (see, for example, Grossman et al. 1989).

In short, a duopolistic scale – “high” or “low” – is needed to assess the practical relevance of teaching and learning processes.

References

Deißinger, T. (1995). Das Konzept der „Qualifizierungsstile“ als kategoriale Basis idealtypischer Ordnungsschemata zur Charakterisierung und Unterscheidung von „Berufsbildungssystemen“. Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik 97(4), 367-387.

Busemeyer, M., & Trampusch, C. (2012). The comparative political economy of collective skill formation. In M. Busemeyer & C. Trampusch (Eds.), The political economy of collective skill formation (3-38). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Shavit, Y., & Müller, W. (2000). Vocational Secondary Education, Tracking and Social Stratification. In M. Hallinan (Ed.), Handbook of the Sociology of Education (437-452). New York: Springer.

Allmendinger, J. (1989). Education Systems and Labour market outcomes. European Sociological Review 5(3), 231-250.

Pilz, M., & Alexander, P-J. (2011). The transition from education to employment in the context of social stratification in Japan – a view from the outside. Comparative Education 47(2), 265-280.

Müller W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From School to Work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (1-48). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grossmann, P.L., Wilson, S.M., & Shulman, L.S. (1989). Teachers of substance: subject matter knowledge for teaching. In M. Reynolds (Ed.), Knowledge Base for the beginning teacher (23, 36). Oxford: Pergamon.

Typologisation of different national VET systems

Below, we allocate individual countries to the typology for illustrative purposes. The main aim here is to demonstrate how the typologisation works. Consequently, we shall not present each country in detail and will only outline the consequences of each assessment in the context of the dimensions used.

Canada

Even if in Canada the impact of the college programs in VET are more important than in the USA, the overall situation in Canada is more or less similar to the one in the USA (Taylor 2006; Lehmann 2014; Kopatz & Pilz 2015).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Canada | Individualised (low state, low employer activity) | low | low | high |

References

Lehmann, W. (2014). Habitus Transformation and Hidden Injuries: Successful Working-class University Students. Sociology of Education, 87(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0038040713498777

Taylor, A. (2006). The Challenges of Partnership in School-to-work Transition. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 58(3), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820600955716

Kopatz, S., & Pilz, M. (2015). The academic takes it all? A comparison of returns to investment in education between graduates and apprentices in Canada. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 2(4), 308–325. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.2.4.4

China

China can be regarded as a country with a strong state influence on vocational education and training (Pilz & Li 2014). The clear separation of vocational training from general education and training, along with restricted scope for ‘progression’ within vocational education and training, suggest a high level of stratification (Shi 2012). Standardisation in VET is “high”, but training is not highly geared to practice (Shi 2012; Pilz & Li 2014).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

China | State dominance | high | high | low |

References

Pilz, M., & Li, J. (2014). Tracing Teutonic footprints in VET around the world? The skills development strategies of Germen companies in the USA, China and India. European Journal of Training and Development, 38(8), 745–763. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-10-2013-0110

Shi, W. (2012). Development of TVET in China: issues and challenges. In M. Pilz (Ed.), The future of Vocational Education and Training in a changing world (pp. 85–95). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-18757-0_6

France

France, by contrast, is deemed to have a VET system that is primarily state-oriented (Busemeyer & Trampusch 2012, p. 12). Against a backdrop of strongly segmented practice between general and vocational education and training, stratification can be classified as “high” (Géhin 2007). Standardisation is also classified as “high” (Müller & Shavit 1998, p. 14), and teaching and learning processes are strongly theoretically-oriented with a low level of relevance to practice (Brockmann et al. 2008).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

France | State dominance | high | high | low |

References

Busemeyer, M., & Trampusch, C. (2012). The comparative political economy of collective skill formation. In M. Busemeyer & C. Trampusch (Eds.), The political economy of collective skill formation (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

Géhin, J.-P. (2007). Vocational education in France. A turbulent history and peripheral role. In L. Clarke & C. Winch (Eds.), Vocational education. International approaches, developments and systems (pp. 34–48). Routledge.

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From School to Work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 1–48). Oxford University Press.

Brockmann, M., Clarke, L., Méhaut, P., & Winch C. (2011). Knowledge, skills and competence in the European Labour Market – What’s in a vocational qualification? Routledge.

Germany

Many studies single out Germany for its ‘dual’ training system in which the state and companies share responsibility for vocational training (Deißinger 1995; Busemeyer & Trampusch 2012, p. 12). Both stratification and standardisation are categorised as “high” in Germany (Blossfeld 1994; Müller & Shavit 1998, p. 14), while learning processes are geared to practice or actually form part of practice (Blossfeld 1994; Deißinger 1995).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Germany | State and company dominance | high | high | high |

References

Busemeyer, M., & Trampusch, C. (2012). The comparative political economy of collective skill formation. In M. Busemeyer & C. Trampusch (Eds.), The political economy of collective skill formation (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

Deißinger, T. (1995). Das Konzept der „Qualifizierungsstile“ als kategoriale Basis idealtypischer Ordnungsschemata zur Charakterisierung und Unterscheidung von „Berufsbildungssystemen“. Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 97(4), 367–387.

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From School to Work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 1–48). Oxford University Press.

Blossfeld, H. P. (1994). Different Systems of Vocational Training and transitions from school to career – the German Dual System in Cross-national Comparison. In CEDEFOP (Ed.), The determinants of transitions in youth (pp. 26–36). CEDEFOP.

India

The dominant context in India is one of low levels of state and company influence, even if some Industrial Training Institutes existing (for a fuller account, see Mehrotra 2014; Pilz 2016). Stratification is considered “high”, in particular because of the strict separation between general and vocational training (Singh 2012; Pilz & Li 2014). By contrast, skill formation in the Indian system is dominated by informal structures and processes, with VET institutions, certificates and formal curricula playing only a minor part. As a result, standardisation is classified as “low”, and within this predominantly informal system, learning processes tend to be directly linked to practice (Singh 2012).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

India | Individualised (low state, low employer activity) | high | low | high |

References

Mehrotra, S. (2014). India’s skills callange: reforming vocational education and training to harness the demographic dividend. Oxford University Press.

Pilz, M. (Ed.). (2016). India: Preparation for the World of Work – Education System and School to Work Transition. Springer VS.

Singh, M. (2012). India’s National Skills Development Policy and Implications for TVET and lifelong learning. In M. Pilz (Ed.), The future of Vocational Education and Training in a changing world (pp. 179–211). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-18757-0_12

Italy

Italy has a very differentiated VET system, which can mainly be considered as school-based. The most frequented VET offer is represented by the nationwide school forms of istituti tecnici (technical schools) and istituti professionale (vocational schools) (Blöchle 2015, p. 5). The funding and also the definition of curricula and guidelines for teacher education is regulated by the state and his national educational ministry, so that we can determine a strong state influence and a high standardisation level (Blöchle 2015; Eurydice 2019). Because vocational education still does not enjoy a positive image within society and it’s more preferred to take part in the general education system, stratification may be high (Ballarino & Panichella 2016, p. 170; Polesel 2006, pp. 551-554). Considering the practice of learning in these two school forms mentioned above, the teaching is still characterised by a teacher-centred type of teaching (Blöchle 2015, p. 5; OECD 2017, pp. 110-111), even though Italy has tried hard to improve the practice of learning with numerous school reforms during the last years – for example the Buona Scuola (good school) (OECD 2017, p. 80).

| Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning |

Italy | State dominance | high | high | low |

References

Eurydice. (2019). Italy: Overview. Retieved February 13, 2019, from https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/italy_en

Blöchle, S.-J. (2015). Berufsausbildung für Europas Jugend. Länderbericht Italien (Studie). Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln. https://www.iwkoeln.de/fileadmin/publikationen/2015/248663/Italien_Länderbericht.pdf.

Ballarino, G., & Panichella, N. (2016). Social stratification, secondary school tracking and university enrolment in Italy. Contemporary Social Science, 11(2-3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2016.1186823

Polesel, J. (2006). Reform and reaction: creating new education and training sturctures in Italy. Comparative Education, 42(4), 549–562. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29727805

OECD. (2017). Getting Skills Right: Italy. OECD Publishing.

Japan

Japan’s vocational education and training system is strongly dominated by companies (Thelen & Kume 1999). Stratification can be categorised as “high” if the informal elements of training, which are of importance in Japan, are given appropriate significance (Pilz & Alexander 2011; Kariya 2011). Standardisation is categorised by Müller and Shavit (1998, p. 14) as “high”, although only if the informal mechanisms are taken into account, while teaching and learning processes within companies are geared to practice (Pilz & Alexander 2011).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Japan | Company dominance | high | high | high |

References

Thelen, K., & Kume, I. (1999). The Rise of nonmarket Training regimes: Germany and Japan compared. Journal of Japanese Studies, 25(1), 33–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/133353

Pilz, M., & Alexander, P-J. (2011). The transition from education to employment in the context of social stratification in Japan – a view from the outside. Comparative Education, 47(2), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.555115

Kariya, T. (2011). Japanese solutions to the equity and efficiency dilemma? Secondary schools, inequity and the arrival of ‘universal‘ higher education. Oxford Review of Education, 37(2), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.559388

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From School to Work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 1–48). Oxford University Press.

Mexico

In Mexico the situation is quite similar to the one in India. General and academic education is strictly separated from the vocational track. The VET system is very small by number of participants and partially shaped by the different provinces in Mexico to meet their own demands. The formal VET system is predominantly located in state regulated vocational institutions with low connection to the working life. But the major vocational training, which is of interest here, is unorganised and follows a “learning by doing” approach, mostly on the basis of private motivation (Kis, Hoeckel, & Santiago 2009).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Mexico | Individualised (low state, low employer activity) | high | low | high |

References

Kis, V., Hoeckel, K., & Santiago, P. (2009). Learning for Jobs– OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training: Mexico. OECD Publishing.

USA

Within the skill formation approach, the USA is seen as having a liberal approach with a low level of state and company influence and a high level of individual influence (Busemeyer & Trampusch 2012, pp. 12-14). Both stratification and standardisation are characterised as “low” (Müller & Shavit 1998, p. 14). At micro-level, there is a strong practical orientation to “learning by doing” at the workplace if college courses, which tend to focus more on general training, are excluded (Zirkle & Martin 2012) and the widespread model of skill development at the workplace is given priority (Barabasch & Rauner 2012).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

USA | Individualised (low state, low employer activity) | low | low | high |

References:

Busemeyer, M., & Trampusch, C. (2012). The comparative political economy of collective skill formation. In M. Busemeyer & C. Trampusch (Eds.), The political economy of collective skill formation (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From School to Work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 1–48). Oxford University Press.

Zirkle, C., & Martin, L. (2012). Challenges and oppurtunities for Technical And Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in the United States. In M. Pilz (Ed.), The future of Vocational Education and Training in a changing world (pp. 9–23). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-18757-0_2

Barabasch, A., & Rauner, F. (2012). Work and Education in America: The Art of Integration. Springer.

Norway

In the context of IVET, the Norwegian "2+2 model" represents the most frequently offered and chosen training programme and is constituted by a two-year school-based and company-based training component respectively (Haukas & Skjervheim, 2018, pp. 13-16; Hiim, 2017, p. 2). For this training programme, a predominant state influence can be established, which manifests itself, among other aspects, in the subsidisation of training companies, the monitoring of school and company quality standards, and the regulation and organisation of final examinations (Haukas & Skjervheim, 2018, pp. 10, 37, 42-49; Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education, 2018, pp. 6-10). The close linkage of general education and vocational learning content allows for the transmission to general education programmes (Haukas & Skjervheim, 2018, p. 15; Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education, 2018, pp. 11-12). It is possible to start a higher education programme following the "2+2" model" after completing an additional year of supplementary studies (Haukas & Skjervheim, 2018, pp. 13, 19-20). In addition to temporal and content-related specifications, the nationally standardised curricula for all vocational fields also include identical regulations regarding the share of general education and vocational subjects as well as possible specialisations (Haukas & Skjervheim, 2018, pp. 14-19). In addition to practical exercises in the first two years of training, a high level of practical orientation can be noted in particular for the subsequent two-year in-company part of the vocational programmes, as in this time the trainees are actively involved in the companies’ work processes (Haukas & Skjervheim, 2018, p. 17; Hiim, 2017, p. 2).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Norway | State dominance

| Low | High | High |

References:

Haukås, M., & Skjervheim, K. (2018). Vocational education and training in Europe – Norway. Cedefop ReferNet VET in Europe reports.

Hiim, H. (2017). Ensuring Curriculum in Vocational Education and Training: Epistemological Perspectives in a Curriculum Research Project. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 4(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.4.1.1

Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (2018). Guidance and outreach for inactive and unemployed. Norway. Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (Cedefop ReferNet Norway).

Finland

Regarding the number of participants in IVET, the three-year school-based training programmes, with a frequency of approx. 82% (as of 2018), are of particular importance in the Finnish VET system (Official Statistics of Finland, 2021). For these training programmes, a predominant state influence can be established, which is reflected in their funding, management as well as control (CEDEFOP, 2019b, pp. 25, 27-28, 31-32, 37, 41). A salient feature here are personal competence development plans, which allow individual recognition of prior learning and thus also shorten the duration of training (CEDEFOP, 2019b, pp. 5, 27-28, 32-33; Koukku et al., 2020, p. 6). ‘Dead ends’ are prevented due to the multiple opportunities for crediting previous learning pathways and the acquisition of educational certificates for individual modules (CEDEFOP, 2019b, pp. 5, 24, 27-30, 56-57). In addition, a degree in these training programmes entitles the student to enter higher education studies (CEDEFOP, 2019a, p. 28), which also generates a high degree of permeability. Despite possible individualisation through the personal competence development plans, the school-based training programmes lead to the acquisition of recognised vocational qualifications, the qualification requirements of which are specifically based on the European credit system for VET as well as numerous compulsory modules (CEDEFOP, 2019a, p. 1; CEDEFOP, 2019b, pp. 5, 28, 54; Koukku et al., 2020, p. 13). The amount of work-based learning varies by personal competence development plan and is not regulated uniformly (CEDEFOP, 2019b, pp. 28, 35). Both the acquisition and demonstration of required competencies take place in working life-relevant learning environments and on-the-job (CEDEFOP, 2019b, pp. 5, 30, 35; Koukku et al., 2020, p. 6).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Finland | State dominance

| Low | High | High |

References:

CEDEFOP (2019a). Spotlight on VET. Finland. European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop). https://doi.org/10.2801/58503

CEDEFOP (2019b). Vocational education and training in Finland. Short Description. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2801/841614

Koukku, A., Lappi, O., & Paronen, P. (2020). Vocational education and training for the future of work. Finland. The Finnish National Agency for Education (Cedefop ReferNet Finland).

Official Statistics of Finland (2021). Appendix table 2. Students in vocational education by type of education 2018. Stat Fi. https://www.stat.fi/til/aop/2018/aop_2018_2019-09-27_tau_002_en.html

Sweden

Within the Swedish VET system, the three-year school-based training programmes are the most frequented programmes in IVET (as of 2017/18: approximately 89% of all VET participants) (CEDEFOP & Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019, p. 19; Skolverket & ReferNet Sweden, 2019, pp. 15, 17). The Swedish government and the Swedish National Agency for Education are primarily responsible for the development of regulations, the definition of framework conditions and their funding, so that a predominant state influence can be established for these training programmes (CEDEFOP & Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019, pp. 19-20, 24, 34). This becomes particularly clear in the context of the additional funds that the state provides to the municipalities in order to achieve a uniform training quality across the country (CEDEFOP & Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019, p. 24). The modular structure of VET programmes allows both for transition between general education and vocational education programmes as well as the adaption of training programmes to local business needs (CEDEFOP & Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019, pp. 4, 21; Kuczera & Jeon, 2019, p. 24; Skolverket & ReferNet Sweden, 2019, p. 17). By completing basic modules, which are also integrated into general education programmes, it is possible to enter higher education programmes subsequently (CEDEFOP, 2021; Kuczera & Jeon, 2019, pp.17-18; Skolverket & ReferNet Sweden, 2019, pp. 15-17). The curricula as well as the modular structure of VET programmes are standardised across the whole country (CEDEFOP & Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019, p. 21; Skolverket & ReferNet Sweden, 2019, p. 16). The proportion of work-based learning in the considered school-based training programmes ranges from 15% to 49% (CEDEFOP & Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019, p. 44; Kuczera & Jeon, 2019, pp. 9-10, 54-56; Skolverket & ReferNet Sweden, 2019, p. 15, 17).

Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

Sweden | State dominance

| Low | High | High |

References:

CEDEFOP (2021). Apprenticeship education in upper secondary school (ISCED3). Gymnasial lärlingsutbildning. Sweden. Cedefop Europa. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/data-visualisations/apprenticeship-schemes/scheme-fiches/apprenticeship-education-upper-secondary

CEDEFOP, & Swedish National Agency for Education (2019). Vocational education and training in Europe. Sweden. System description. Cedefop and Swedish National Agency for Education (ReferNet Sweden).

Kuczera, M., & Jeon, S. (2019). OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training.

Vocational Education and Training in Sweden. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9fac5-en

Skolverket, & ReferNet Sweden (2019). Vocational education and training in Europe. Sweden. Skolverket (Cedefop ReferNet Sweden).

United Kingdom

In the skill formation approach, the vocational education and training system in the United Kingdom (UK) is described as a liberal approach with little influence from the state and companies, but a high degree of influence from the individual (Busemeyer, 2013, p. 6). Stratification is described as low, and the same applies to standardisation (Müller & Shavit, 1998, p. 14). At the micro level, a strong practical orientation in the context of learning by doing in the workplace can be identified if the numerically small proportion of apprenticeships and college education focused on general education are excluded and the focus is instead placed on widespread on-the-job training (cf. Crouch, Finegold & Sako, 1999; cf. Fuller & Unwin, 2013; cf. Pilz, 2009).

| Skill formation | Stratification | Standardisation | Practice of learning | |

| UK | Individualised (low state, low | Low | Low | High |

References:

Busemeyer, M. (2013). Fachkräftequalifizierung im Kontext von Bildungs- und Beschäftigungssystemen. Berufsbildung in Wissenschaft und Praxis, 42(5), 6-9.

Crouch, C., Finegold, D., & Sako, M. (1999). Are Skills the Answer? The political economy of skill creation in advanced industrial countries. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Fuller, A., & Unwin, L. (2013) (Hrsg.). Contemporary Apprenticeship – International perspectives on an evolving model of learning. Oxon/New York: Routledge.

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From School to Work: a comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 1-48). Clarendon Press.

Pilz, M. (2009). Initial vocational training from a company perspective: a comparison of British and German in-house training cultures. Vocations and Learning, 2(1), 57-74.